In children’s mental health, it is often the little things that are the big things. Let’s take anxiety, for example. Children can have school refusal behaviours and when you dig down they might be anxious about:

- going out to play and finding a friend

- having to eat everything in their lunch box before playing

- knowing what to say or when to laugh in ‘that’ group of friends

- playing with the right person to stay ‘in’

We have to look very carefully at issues as they arise in children as often there is a surprisingly specific stimulus that has grown into something much. much bigger than they are able to give voice to or find a solution to. Patterns of anxiety are not always rational. As adults we can say to children, “Don’t worry about that – that’s not important.” or “Do you really think that’s going to happen?” In that child’s mind it is real and it is important and huge behavioural complications (like school refusal) can result.

What we do know about children (and adults too) is that even very few repetitions of the same pattern of thinking or behaving rapidly become hard wired. For example, a little person might go to join in a game and the group refuses entry. The following day, the child approaches the group again – this time a little tentatively and if the group again refuses entry to the game the child’s thinking will start to tell the story of ‘always’ being excluded, of ‘no one’ liking them and of it being not fair to be left out. It might then follow that the child excludes themselves from games on the basis that no one ever lets them play and they’re always left out. This can lead to problems focusing in the classroom and behavioural challenges at home. Something very simple can lead to a very challenging chain of behaviours that follow.

If we teach children skills early in their lives to manage their patterns of thinking and to respond differently to challenges in their social and learning environments there is a strong probability that these skills become hard-wired. That means when bigger social issues and bigger learning challenges occur, children already have a pattern of thinking and behaving that leads to them decatastrophising events, being persistent, showing resilience when things don’t go their way. Together, these are very important preventative factors in later mental health issues.

The question is, how do we teach children these skills? In Social and Emotional Learning we teach children social skills (improving social skills and managing social issues), emotional self-regulation skills as well skills that promote learning resilience. Teachers are required (in Australia) to teach these skills a part of the Health & Physical Education component of the curriculum in a unit of work entitled Personal and Social Capabilities. Direct, explicit teaching of these skills. Allied Health Therapists and Psychologists often tackle the same skills in small group therapy. And parents should be including this as part of their daily dialogue with their children.

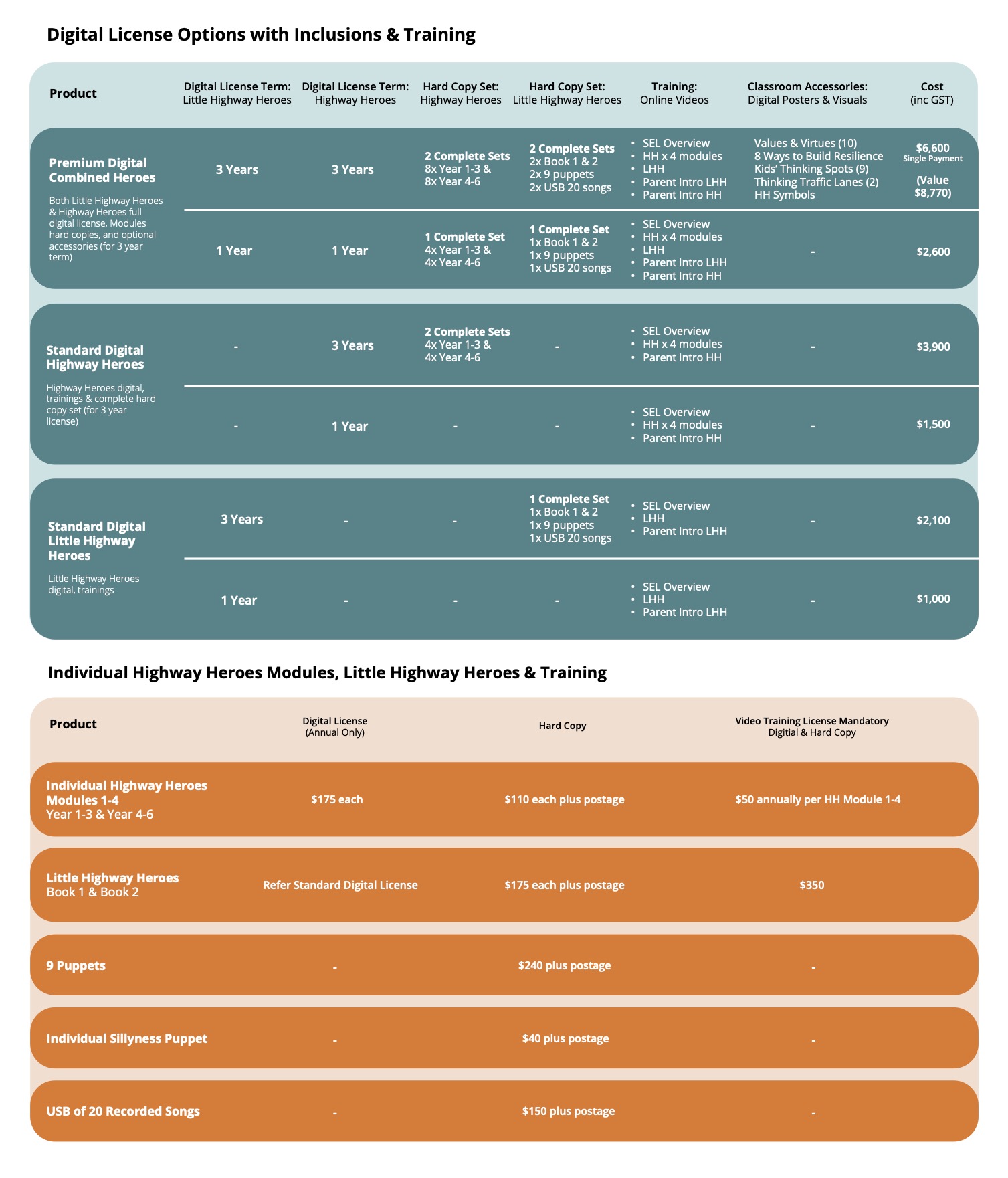

At BEST Programs 4 Kids we have written resources for teachers, allied health professionals and psychologists called the Highway Heroes; Smart Life Skills 4 Kids Modules. There are also resources for parents called the Kids’ and Parents’ Notebooks which step kids and parents through the tricky social stuff and give practical, clinically proven strategies to change thinking and behaviours. I invite you to have a look through our website and see what you can do today to help the little things stay the little things for kids. We’re all part of finding solutions for kids to reduce the soaring levels of mental health issues in our teens and young adults.